By Chris Jones/Active Senior’s Digest

The McLaughlin’s were a powerful family, that much is certain. Their history is filled with triumphs and sorrows, just like any other family. The same can be said of their home, Parkwood Estate.

The McLaughlin’s were a powerful family, that much is certain. Their history is filled with triumphs and sorrows, just like any other family. The same can be said of their home, Parkwood Estate.

Today, Parkwood is used as a tourist attraction, as well as a place to film movies, such as X-men and Billy Madison.

But before that, it was home to one of the most influential families in Oshawa’s hsitory: the McLaughlin family.

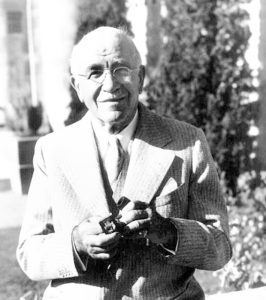

Robert Samuel McLaughlin, the patriarch, and his wife,

Adelaide, along with their five daughters, resided at the sprawling estate located near what are now Simcoe and Adelaide streets.

According to the family’s official website, Sam, as he preferred to be called, only joined his father’s business, alongside his older brother, George, after he had spent time outside of Oshawa.

During his time away, Sam gained experience in the “manufacture of vehicles, working in Watertown, Syracuse, and Binghamton, New York,” according to the Parkwood website.

Upon his 21st birthday, Sam and his brother were made partners at McLaughlin Carriage Works, which had become the largest carriage company in the British Empire. Sam was then named the chief designer of all carriages and sleighs.

However, Sam’s attention was pulled elsewhere, as the automobile had begun to make its rise in popularity.

“He and his brother George persuaded their father that the future of the firm lay in motor car production,” the Parkwood website reads.

In 1908, Sam sold his company and was named the president of the Canadian operation, and vice president of the parent corporation, with his brother, George, being named vice president of the Canadian operation.

In their first attempt at making a unique and original motorcar of their own, the McLaughlin Motor Car Company failed due to the chief engineer on the project falling ill.

Fortunately, their second attempt at making a unique vehicle that was all their own was a success, and McLaughlin-Buick began production in 1908.

The vehicle itself was made and designed in Canada, and it used an engine that was supplied by American company Buick.“The arrangement was brokered through an agreement with

Sam’s friend William Durant, one of the original ‘architects’ of General Motors,” reads the website.

It was then in 1915, that a similar arrangement was reached to begin production of Chevrolets.

After the deal with Buick reached its end, the thriving McLaughlin Motor Car Company suddenly had no way to replace them. It was then they decided to join forces with the brand new General Motors (GM) Company, and an Oshawa legend was created.

The move ensured the long-term success of the McLaughlin Motor Car Company, and guaranteed that production would remain in Oshawa for some time.

Sam would remain president until 1945 when he stepped down and was named chairman of the board, a position he held until the day he died in 1972.

However, Sam was a businessman, and people often forget that, according to Samantha George, the curator of the Parkwood Estate.

When GM workers went on strike in 1937, it was not taken kindly by the company.

“Sam was a business figure, and like many of his contemporaries, he didn’t want unions in General Motors of Canada,” George recalls.

George says this was a fact that was long ignored, as she says, “For years and years, Parkwood failed to chat about the 1937 GM strike and Sam’s role in trying to bust the strike and union. That is not something that we should shrink away from.”

“It’s historic fact too, and offers insight into labour history as well as telling the richer story of Oshawa society at the time,” she says.

The 4,000 workers who participated in the strike were asking for an eight hour work-day, better wages, better working conditions, a seniority system, as well as recognition of their union, United Automobile Workers. This final demand was what caused the strike.

Despite the strike, “[Sam’s] efforts to keep organized labour out failed,” says George.

GM’s Canadian headquarters still remains in Oshawa to this day, and is, in fact, a unionized work place. It can be found at 1908 Colonel Sam Drive.

Before the strike, and before he joined his father’s company, Sam met Adelaide Louise Mowbray in February 1898.

The two were married on the Mowbray family farm, and then honeymooned in New York.

Adelaide herself was born in 1875 in Kinsale, Ontario to Ralph Mowbray and Victoria Nutting.

Adelaide’s mother was able to trace their lineage all the way back to the famed ship, the Mayflower.

Adelaide would attend teachers college in Ottawa, and after graduating, would go on to become a schoolteacher in Whitby.

One day while attending church, a chance meeting would change her life forever when Sam noticed her singing in the choir.

According to the Parkwood website, when asked about the day he met his wife, Sam said, “The only person I really saw in the church that day was a vision of beauty in the choir.”

After only two dates, Sam and Adelaide were head-over-heels in love, and he asked her to marry him. They were married in 1898, and subsequently moved into their new home on King Street. Adelaide would leave her job as a schoolteacher behind.

They were quick to start a family with their first daughter, Eileen, being born in 1898.

Eileen would then be followed by Mildred in 1900, Isabel in 1903, Hilda in 1905, and finally, Eleanor in 1908.

At the time of their marriage, Sam was still working for his father. However, 10 years later, Sam and George began the automobile business alongside their father.

However, Adelaide would not simply be outdone by her husband and let him do all of the work.

“Women like Adelaide were not satisfied to stay at home,” reads the website. “She used her skills and societal influence in creating ways to benefit society through charitable work.”

While her husband was a businessman, Adelaide was a philanthropist.

The Oshawa General Hospital was very important to her, as she helped in seeing the hospital opened in 1910, only two years after giving birth to their youngest child, Eleanor.

Adelaide also became the first president of the hospital’s Ladies Auxiliary, and she would hold onto that position until her death in 1958.

She would use a fundraising technique that was called the ‘Talent Dollar project’ according to the website.

With this technique, she would take one dollar from the treasury, and she would give it to a member of the Ladies Auxiliary and tell them to “make it grow.”

The website says that the profits from this would range anywhere from one dollar to $90.

Adelaide was also very active in the Girl Guide Association, an organization that still exists to this day and helps young girls to feel empowered in a safe environment.

Together, Sam and Adelaide donated the white Guide House to the association in 1948, which it owned until 2014.

According to the Oshawa Museum, Adelaide was also a big supporter of several other organizations, such as the YWCA, the Ontario Historical Society, Women’s Welfare League, Victorian Order of Nurses, and many others.

Adelaide also served as the honorary president of the Canadian Home and School and Parent-Teacher Federation.

However, Adelaide’s life wasn’t all about charity work, as she also adored golf. She was the president of the Canadian Women’s Golf Association from 1937 to 1956. She was also a lifelong member of the Toronto Ladies Golf and Tennis Club, as well as the Seigniory Club in Quebec.

Adelaide also enjoyed beating her husband at billiards, and would spend her nights either doing needlepoint, or playing Scrabble and bridge.

“She was a fierce competitor who insisted on collecting any bets – no matter how small,” reads the Parkwood website.

One aspect of the world that Adelaide adored was flowers. Over her life, she studied them and grew to become an expert on them according.

Due to her love of flowers, some Parkwood rooms that were particularly important to her were the gardens and greenhouses on the property.

Adelaide was the hostess of the annual Chrysanthemum Tea at Parkwood Estate, an event that would attract approximately 800 people every year.

Adelaide died in 1958 at the age of 83, while Sam died when he was 100. Their five daughters, who have all since passed, survived them. Isabel was the last surviving child of the pair and she died in 2002 at the age of 99.

“Several generations of locals revered and almost conferred sainthood onto Sam McLaughlin, forgetting that although he was generous and a remarkable figure, he was human, and both sides must be interpreted,” says George.

From George’s point of view, it must be remembered that, while Sam had a positive impact on Oshawa that is still felt to this day, he also made questionable choices, such as his decision to not support the workers during the GM strike in 1937.

Sam and Adelaide’s presence is still felt in Oshawa to this day. There are public schools named after them, as well as streets and museums. And GM is still a mainstay in the Oshawa community and economy.

The estate is a monument to Oshawa’s history, both for good and for bad.

It’s where a man who often seems revered as a saint spent the latter half of his life. It’s a monument to all that Oshawa has been through.

For those who don’t live in or around Oshawa, Parkwood is simply “Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters” from the X-Men movie franchise.

For those who do live in Oshawa, and especially for those who work in the GM plant on Stevenson Road, it’s a monument to Robert Samuel McLaughlin, a man largely responsible for the auto industry’s presence in the city.

Driving past Parkwood, you can catch a glimpse of the front yard. For a split second, you can see the house that feels like the centre of the city.

You can catch a brief view of the well-kept front yard and the pillars in front of the door that harken back to ancient Rome and Greece.

For a lot of people, this house is their dream. Almost everyone wants to live in a big mansion.

Just like Sam, Parkwood Estate is seen as saintly. There’s something about the estate that causes the people of Oshawa to develop a longing look in their eyes.

However, while many Oshawa citizens will look at Parkwood Estate in reverence, they don’t necessarily know the history of the building itself.

According to Samantha George, the curator of Parkwood Estate, the estate itself was completed in 1917, and the earliest blueprints are from 1914.

George says false claims are one of the things that those at Parkwood are trying to combat.

“One of the things we combat about Parkwood is the local legends and the romanticization of the property by the public. On our social media forums we have an ‘Ask Sam’ column where the public can post questions about the estate and I answer them.”

George says topics that are broached range anywhere from the McLaughlin’s themselves to the construction materials that were used to build the estate.

Parkwood Estate was built on top of what was once known as “Prospect Park.”

“Parkwood was born of a collaboration between Sam McLaughlin, his wife Adelaide, and the best artists, architects and landscape designers of the time,” reads the Parkwood website.

It was built shortly before Sam founded and became president of GM Canada. The design was inspired by early 20th century Beaux-Arts design.

Beaux-Arts architectural style is taught at Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and it draws upon the values of French neoclassism. Gothic and Renaissance influences can also be found in the style, and it uses modern materials, such as glass and iron.

It was a style that was prominent in France at the end of the 19th century.

“The mansion represents a rare residential design by architects [Frank] Darling and [John] Pearson, the team who are widely credited as an outstanding influence on Canadian institutional architecture,” reads the website.

“The mansion represents a rare residential design by architects [Frank] Darling and [John] Pearson, the team who are widely credited as an outstanding influence on Canadian institutional architecture,” reads the website.

Darling and Pearson were responsible for notable buildings such as the Toronto General Hospital and the Royal Ontario Museum.

Pearson himself designed the new Centre Block of Parliament in 1917.

The style of the house itself is Classic Revival. It also has some Georgian features.

Two additions were added to the house in the 1930s and 1940s. An award-winning architect out of Toronto named John M. Lyle designed them, and they were two interior spaces that were inspired by Art Deco style.

“While inspired by the historic villas, chateaux and stately homes of Europe, the McLaughlin’s fashioned their estate to include the newest trends and innovations,” reads the website. “The design of Parkwood’s architecture, interior decorations and garden landscapes are all imbued with a 20th century style and a distinctly North American sensibility, including some outstanding examples of art moderne.”

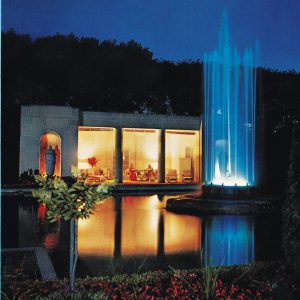

Part of the overall design was comfort, so while these may not have been common at the time, the McLaughlin’s did not hold anything back in their design. The house itself contained a central clock network, in-house telephone system, a central vacuum system, remote controlled consoles for an outdoor lighting system, air conditioning, climate-controls for the art gallery, a humidification system, sophisticated heating and water systems, a walk-in fridge, and an elevator.

On top of all of those features, “Parkwood was designed for entertaining, with unusual recreational features, amenities and novelties to be enjoyed by the McLaughlin’s and their many guests. These remarkable features continue to delight today, including a squash court, a grand conservatory, a rare Aeolian organ, a heated indoor swimming pool, a bowling alley and a games room,” the website reads.

One place that the McLaughlin’s would entertain their guests was the garden which has been featured in a number of feature length films, such as Billy Madison and 12 Monkeys.

While living at the estate, the McLaughlin’s interest in horticulture and landscaping could be seen through the 11 greenhouses and staff of 24 gardeners.

The McLaughlin’s sought out the best when it came to their garden. In the 1910s, they hired Harries and Hall, the famed husband and wife team of Howard and Lorrie Dunington-Grubb in the 1920s, who were the founding members of the Society of Landscape Architects and Sheridan Nurseries – which is still going strong today. And to top it off, they hired Lyle in the 1930s.

The McLaughlin’s sought out the best when it came to their garden. In the 1910s, they hired Harries and Hall, the famed husband and wife team of Howard and Lorrie Dunington-Grubb in the 1920s, who were the founding members of the Society of Landscape Architects and Sheridan Nurseries – which is still going strong today. And to top it off, they hired Lyle in the 1930s.

“The Parkwood gardens have references to the great gardens of England and Europe, but with a 20th century spirit,” reads the website. “Much of the landscape design draws inspiration from the English Arts & Crafts gardening movement. This style called for a high degree of formality near the house, dissolving into less formal presentation with distance from the house, including a broad expanse of immaculate lawn.”

The perimeter of the house uses dense, woodland borders and cedar hedges to help sub-divide the landscape into formal garden spaces, recreation areas, and farming space.

In the farming space, one would find fresh cut flowers, fruit and vegetables.

The hedges were used to prevent the viewing of the entire landscape all at once. They were “complimented by garden gates beckoning visitors to proceed through a sequence of garden views and experiences.”

In the 1920s, the Dunington-Grubb’s created outdoor “garden rooms” that were called the Italian Garden, Sundial Garden, Summer House and the Sunken Garden, amongst many other contributions to the tennis court and other areas.

Finally, between 1935 and 1936, Lyle created the Formal Garden, for which he was awarded the bronze medal from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada.

According to the website, the gardens have been conserved so that they appear the way they did in the 1930s, when the McLaughlin’s still lived there.

The interior of the house is maintained so as to appear that the McLaughlin’s still live there today.

“Complete room settings showcase the designers’ works and illustrate the lifestyle of the wealthy family as well as the hospitality that they extended to guests,” reads the website. “Crystal and china, silver, linens, books, family photographs and memorabilia, needlework and trophies are all preserved and displayed in their original settings. The collection is complete down to the monogrammed linens, creating an impression that the family is still in residence.”

There are murals adorning the interior, some of which were from two Canadian artists, Frederick Challener and Frederick Haines.

Alongside the murals, there are sparkling chandeliers, European and Canadian fine art, photographs and other family mementos.

George believes that every room in the house is special. She says that’s because of “their architecture, what they say about the family and social trends of the day.”

She says, “[each room’s] location in the house, the décor and the small moveable artifacts located within; the role of the room is significant in commentary about the family.”

George also ponders the interior decorator of the house. She wonders what message they were trying to send in each room. She wants to know what story they were trying to tell.

She also wonders how well the McLaughlin’s embraced what the interior decorators did with the house, as well as how its changed in the 55 years since anyone has lived there.

Each room in the house tells a different story about the family, and one that is important to George.

The website says that there are lavish architectural finishes in carved wood and plaster, as well as decorative plaster ceiling treatments, mantles and fireplaces. There is also marble, tile and wood flooring, as well as “charming architectural novelties such as hidden panels and stairways.”

According to the website, the decorations in the house show an old-world style that blends with new-world art moderne.

Pieces of furniture around the house are from the Louis XVI collection. There are also elaborate window treatments, Oriental carpets and custom-loomed carpets, ornamental metal works, decorative clocks, planters, vases, and innumerable pieces of original artwork.

“Visitors today continue to marvel at the quality workmanship and artistic creativity that is demonstrated throughout each room’s decorations and furnishings,” reads the website. “The Parkwood Foundation and staff take great pride in preserving the inestimable collection for future enjoyment.”